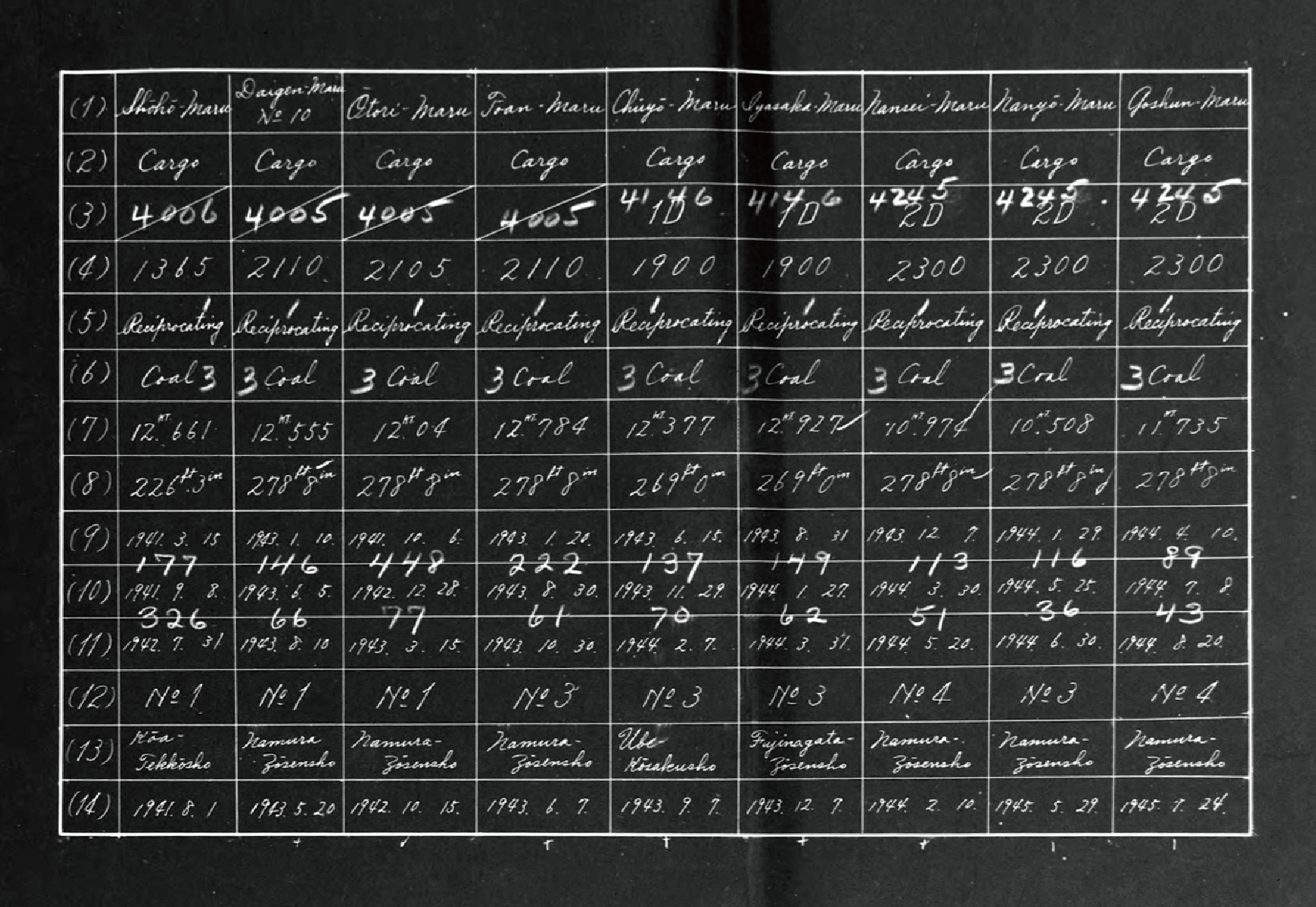

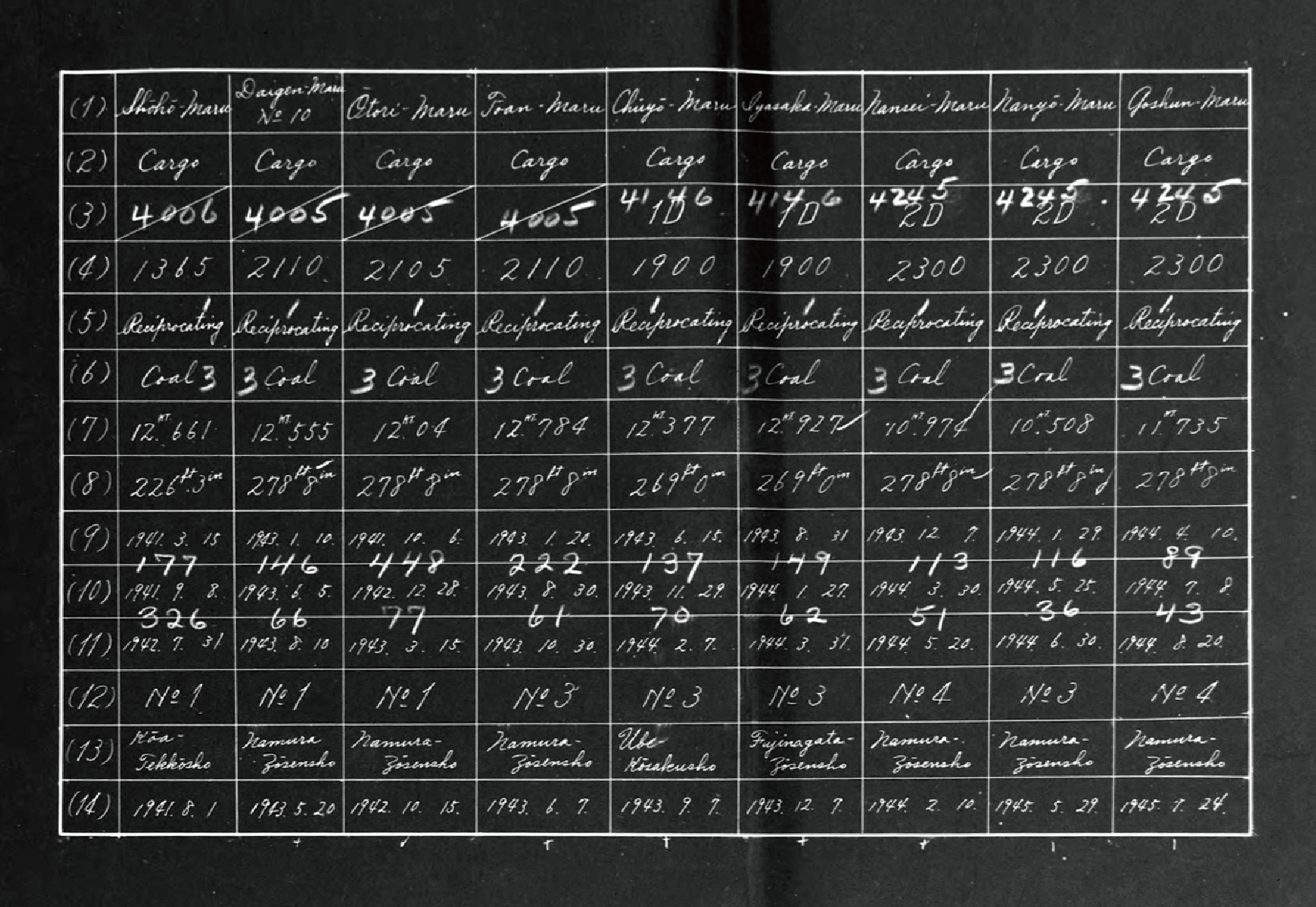

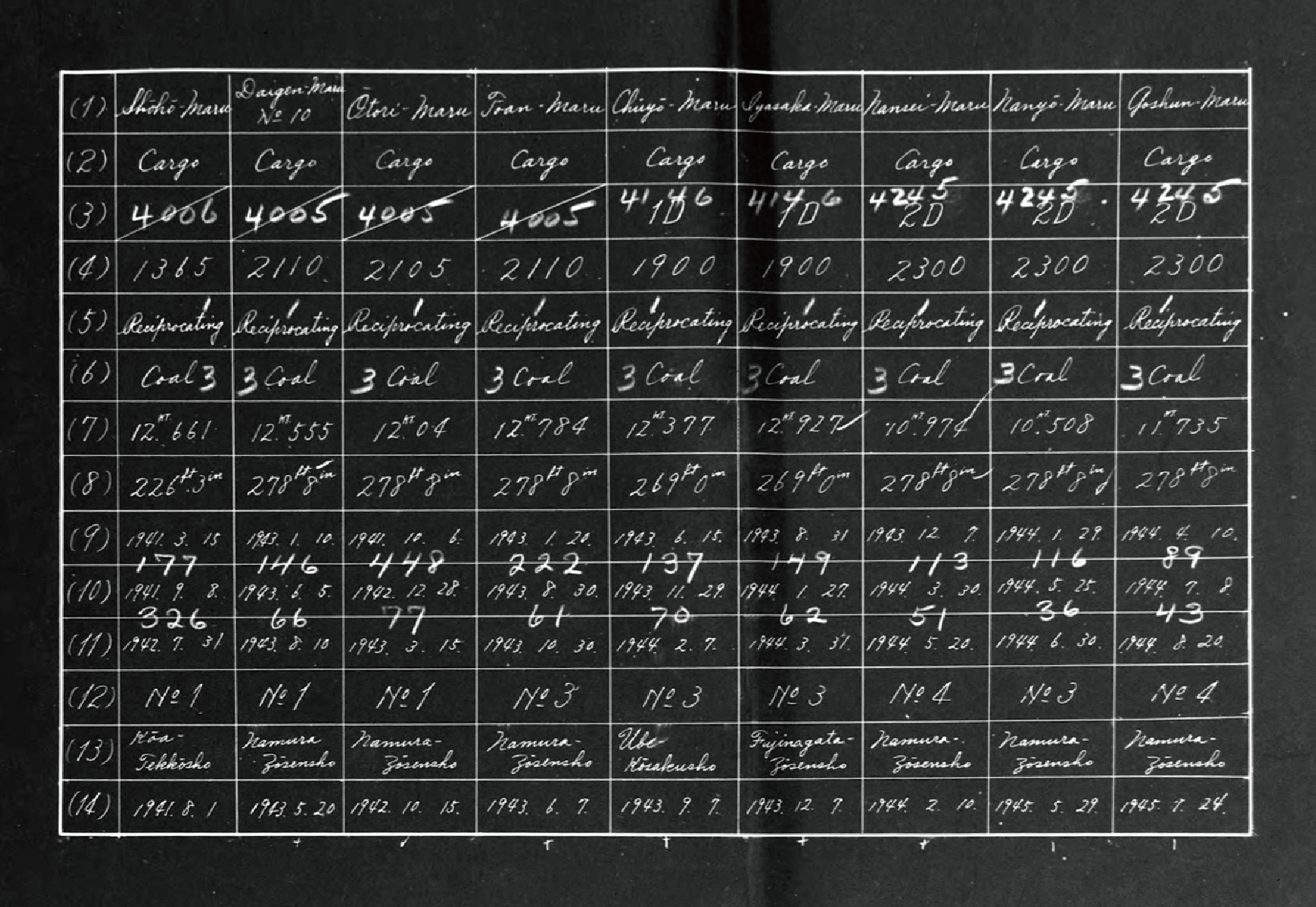

Namura Zosensho-Statistical Report. Report no. 48b (22). Entry 41: Pacific Survey Reports and Supporting Records, 1928-1948. RG243: Records of the United States Strategic Bombing Survey. National Archives and Records Administration, the United States. Data from National Diet Library, Japan.

Project Intersection

In 2007, the Japanese Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry designated the former factory site of Namura Shipyard in Osaka as one of the “33 Heritage Collections of Industrial Modernization.” The site is now utilized for cultural and artistic activities as “a unique space that has been renovated to maximize its ‘potential as a ruin’.” But many of those who currently visit the former factory site for art events and other occasions are unaware of its hidden history. The factory was a site of forced labor, where a total of 803 laborers were conscripted between 1942 and 1945, and 110 Allied prisoners of war were subjected to the servitude during the war. When one confronts this past reality, it would inevitably affect one’s present perception of the old factory space. (Yoshiya Makita, “At the Intersection of the Past and Present: History and Historical Practice on the Street,” Shien 79, no. 2 [2019]: 156. [In Japanese])

Workshop “Intersection I: In-Between Art, History, and the Local”

Field Research Project “Records, Traces, and Memories”

Date: 3 February 2018

Venue: Creative Center Osaka (Old Namura Shipyard, Suminoe-ku, Osaka); waterfront districts in Osaka, Japan

Project Statement

In recent years, the Osaka Bay Area has witnessed a growing number of initiatives aimed at neighborhood revitalization through cultural and artistic programs. By repurposing former factory sites and vacant houses for creative activities, the local government, the culture foundation, and other stakeholders have continued efforts to transform the bay area into a cultural hub for artistic endeavors, thereby revitalizing local communities through the power of art. Behind these initiatives to enhance the “attractiveness” of local communities by promoting art and culture, however, old communal memories of dock laborers have gradually faded into the depths of oblivion. Focusing on the history and memory of the Osaka Bay Area, this project explores the ways to restore the historical experiences of those who have been excluded from the dominant narratives of public memory in the area through artistic practices.

In the first half of the twentieth century, the city of Osaka developed as one of the major centers of the steel and dock industry in Japan. In parallel with the territorial expansion of the Japanese empire, the city attracted a large influx of common laborers from overseas colonies. This project delves into the mechanisms of power and violence that shaped the transnational experiences of various groups who migrated to the Osaka Bay Area through historical inquiry. By examining their lives on the social periphery in the bay area, we seek new modes of artistic practice that would challenge, reshape, and reimagine the local constellation of collective memories. Instead of giving tacit approval to the dominant narratives of public memory established by majority groups in the area, this project highlights the potential for artistic creation to destabilize the foundations of existing public memory from the perspectives of those on the fringes of local society.

Industrial plants along Kizugawa River

Source: Governor’s Office, Graph Osaka (Osaka: Public Information Division, November 1967).

Over the past decades, numerous art projects have aimed to foster close “connections” between their artistic endeavors and local communities, crystallizing into a growing number of “community art” and “memory art” pieces inspired by local history. Yet, the life stories of minority groups have frequently become invisible in these site-specific artworks. Art projects have tended to prioritize maintaining harmonious relationships with local residents and therefore have been inclined to avoid critical reading of history that would provoke confrontations with majority groups in local communities. Consequently, they have often overlooked the exclusive nature of the dominant public memory in these communities and have failed to critically address the tensions between art, history, and society. With a strong aspiration to be “community-based,” these projects have too readily endorsed the prevailing historical interpretations of local communities, inadvertently reinforcing the existing “master narratives” of local history.

This project uncovers the hidden complicity between certain trends in art projects and the conventional narratives of local history and memory in Japan. Reconsidering the seemingly stable identity of local communities through historical research, we seek to illuminate new directions in artistic practices for more critical engagement with social issues. Marked by the harsh violence of colonialism in the past and the advancement of creative initiatives in the present, the Osaka Bay Area offers a unique vantage point to envision new possibilities in socially engaged art and culture.

Workshop “Intersection I: In-Between Art, History, and the Local” (3 February 2018). Photo by Masaki Komori

Workshop “Intersection I: In-Between Art, History, and the Local”

Panelists: Hikaru Fujii, Yuki Harada, Yuki Iiyama, and Sen Uesaki

Moderators: Masaki Komori and Yoshiya Makita

Organizers: Project Intersection Planning Committee (Masaki Komori and Yoshiya Makita); Makita Yoshiya Research Seminar (AY2017-2018), College of Policy Science, Ritsumeikan University

Field Research Project “Records, Traces, and Memories”

“Exploring traces of the past within the present landscape and creating a new constellation of memories through historical records”

Fieldwork and on-site workshop

Moderators: Hikaru Fujii and Yoshiya Makita

Date: 3 February 2018, 10:00-13:30

Place: Taisho-ku and Suminoe-ku, Osaka City, Osaka

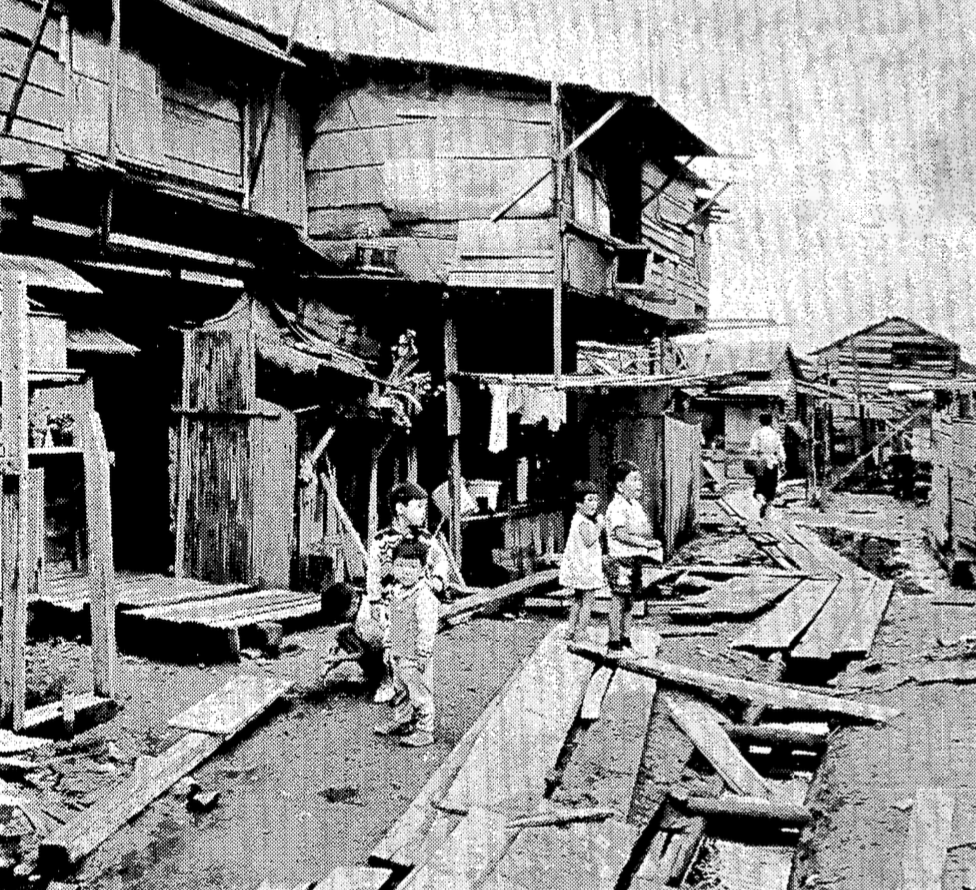

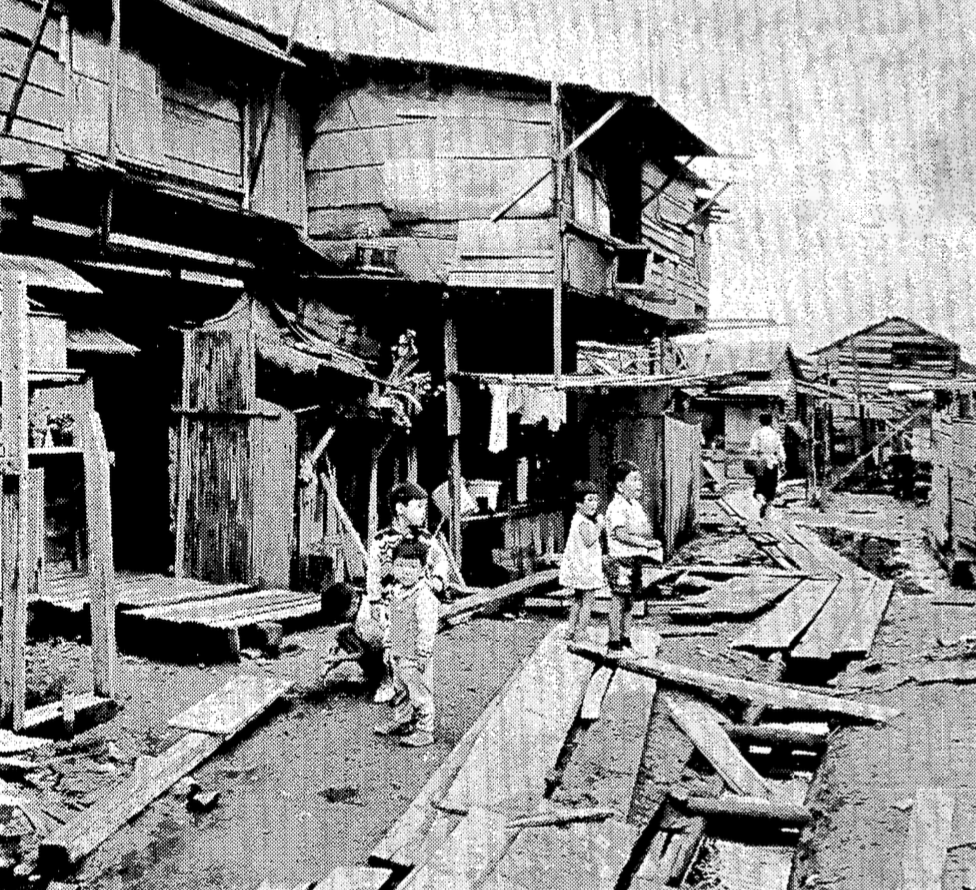

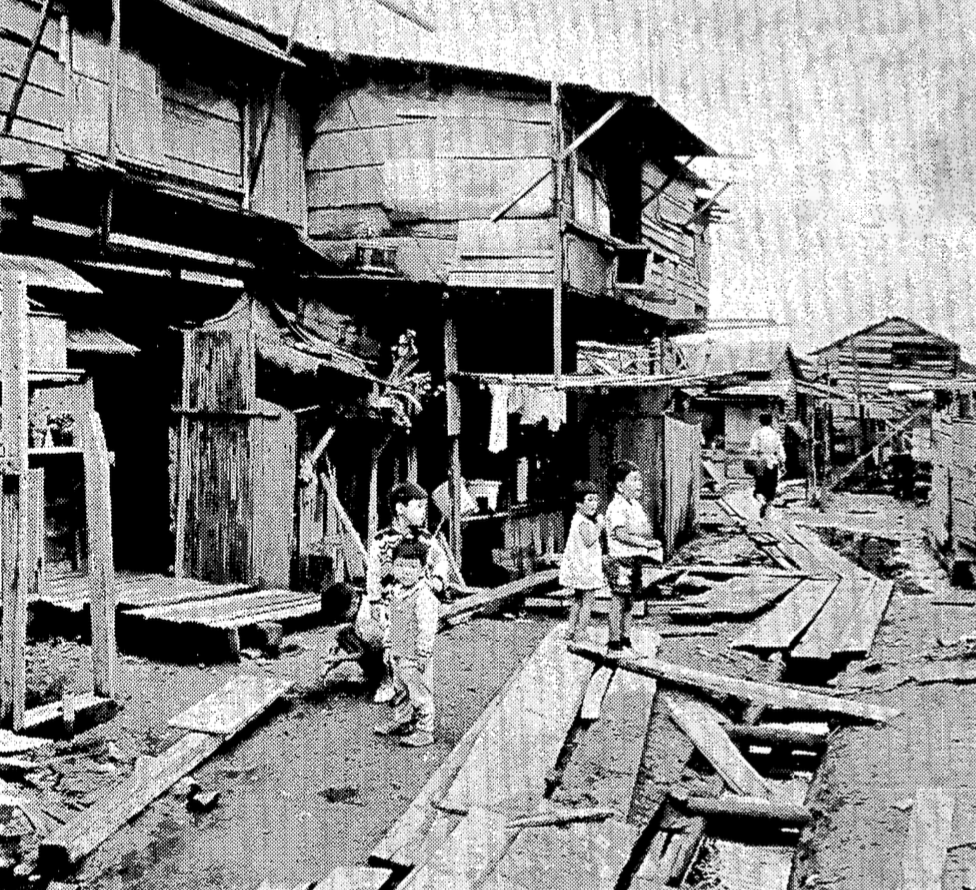

In the southwestern part of Osaka City, there is a block known as “Okinawa Slum” in a corner of Taisho Ward. Shacks are crowded on the marshy land, where about 1,500 people live, packed closely together. Approximately 30% of the residents are from Okinawa. […] Twenty-three years have passed since Japan’s defeat in the previous war. Even after the restoration of independence on Japan’s mainland, the occupation has continued in Okinawa. The island has been left separated from the homeland. For its nine hundred thousand residents, as well as for the entire nation, the reversion to the homeland is a long-cherished dream. But what if the slums are the only refuge for those who left their island and returned to the homeland ahead of others… This reality seems symbolic of a deep divide that lies between the mainland and Okinawa. (Quotes from Asahi Shinbun [15 July 1968]. [a])

“Kubungwa,” an Okinawan village in Taisho Ward, Osaka City, in the 1960s

Source: Asahi Shinbun (15 July 1968).

And there was a vast vacant lot to the east of the village. The lot was called Akaba, a site used for garbage dumping and incineration. A uniquely strong burning smell spread all around. But once I got used to it, I didn’t mind it so much. In fact, this garbage dump is closely related to the lives of people in the Korean village. / Aka meant copper. The Koreans in the village collected and sold copper wire, iron scraps, shards of other metals, and pieces of glass from the ashes and burnt residue. This turned out to be quite a good source of income. (Quotes from Choi Sukeui, Zainichi no Genfukei: Rekishi, Bunka, Hito [Akashi Shoten, 2004], 13. [b])

“Sanoyasu the Devil, Namura of Hell, and Merciless Fujinagata.” This was a catchphrase I often heard. Was this just the cynicism of Osaka folks making fun of the winners, or did it actually reflect some truth? It may sound quite convincing to those who are personally familiar with the shipyards that once stood along Kizugawa River. (Quotes from Kazuo Sugiyama, “Kawasuji no Zosenya: Namura Gennosuke-okina no Sokuseki,” Koseki: Sensho tachi kara Jidai heno Dengon, ed. Kansai Zosen Kyokai [Kansai Zosen Kyokai Soritsu 90 Shunen Kinenshi, 2002], 37. [c])

Lumber workers on water

Source: Osaka City Port Authority, Osakako-Shi 3 (Osaka: Osaka City Port Authority, 1964).

In 1912, I was born as the eldest son of a poor peasant family in North Gyeongsang Province. In 1927, when I was fifteen years old, I came to Japan in search of work. I lived in Osaka, where I worked hard and attended evening classes. It was a difficult time, but I was happy because I was with my family. / Yet, it only lasted for a short period of time. In 1942, a year after the war started, I was taken to Namura Shipyard, a munitions factory in Osaka. The factory was a military-style structure for labor. It was tough for me. (Quotes from Park Seongchaek, “Kako heno Shin no Hansei wo: Osaka Namura Zosen,” Chosenjin Kyosei Renko no Kiroku: Chubu, Tokai Hen, ed. Chosenjin Kyosei Renko Shinso Chosadan [Kashiwa Shobo, 1997], 292. [c])

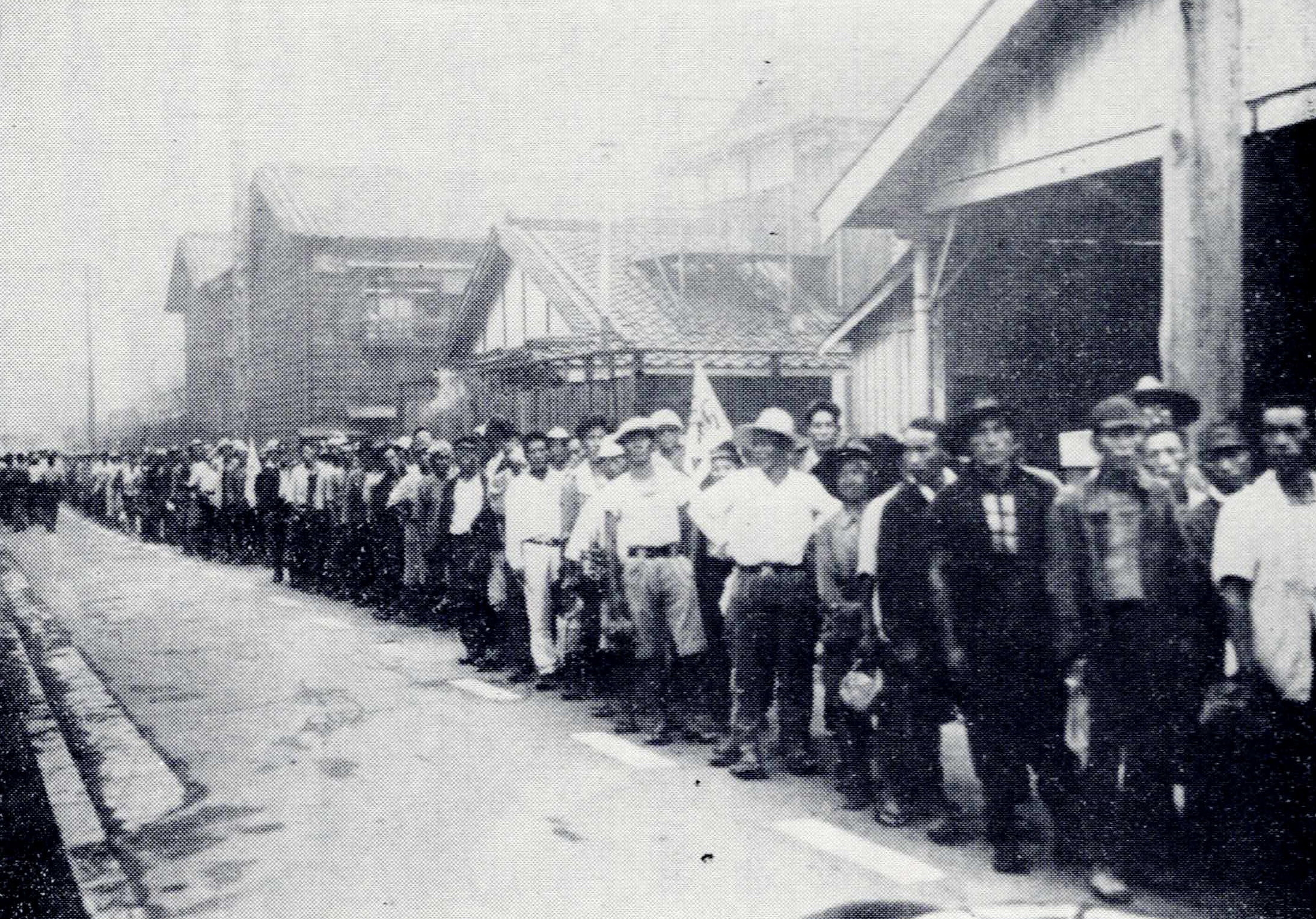

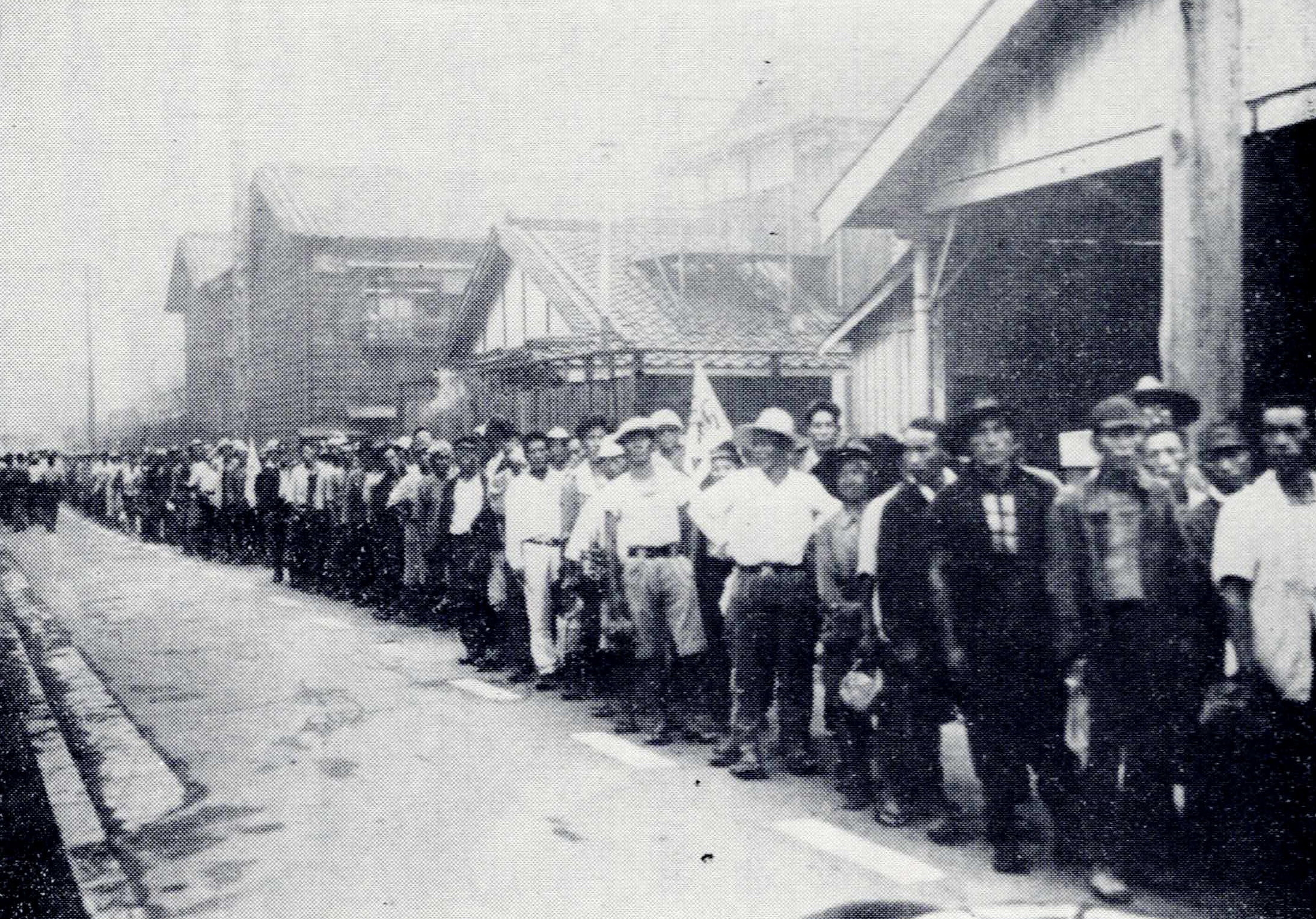

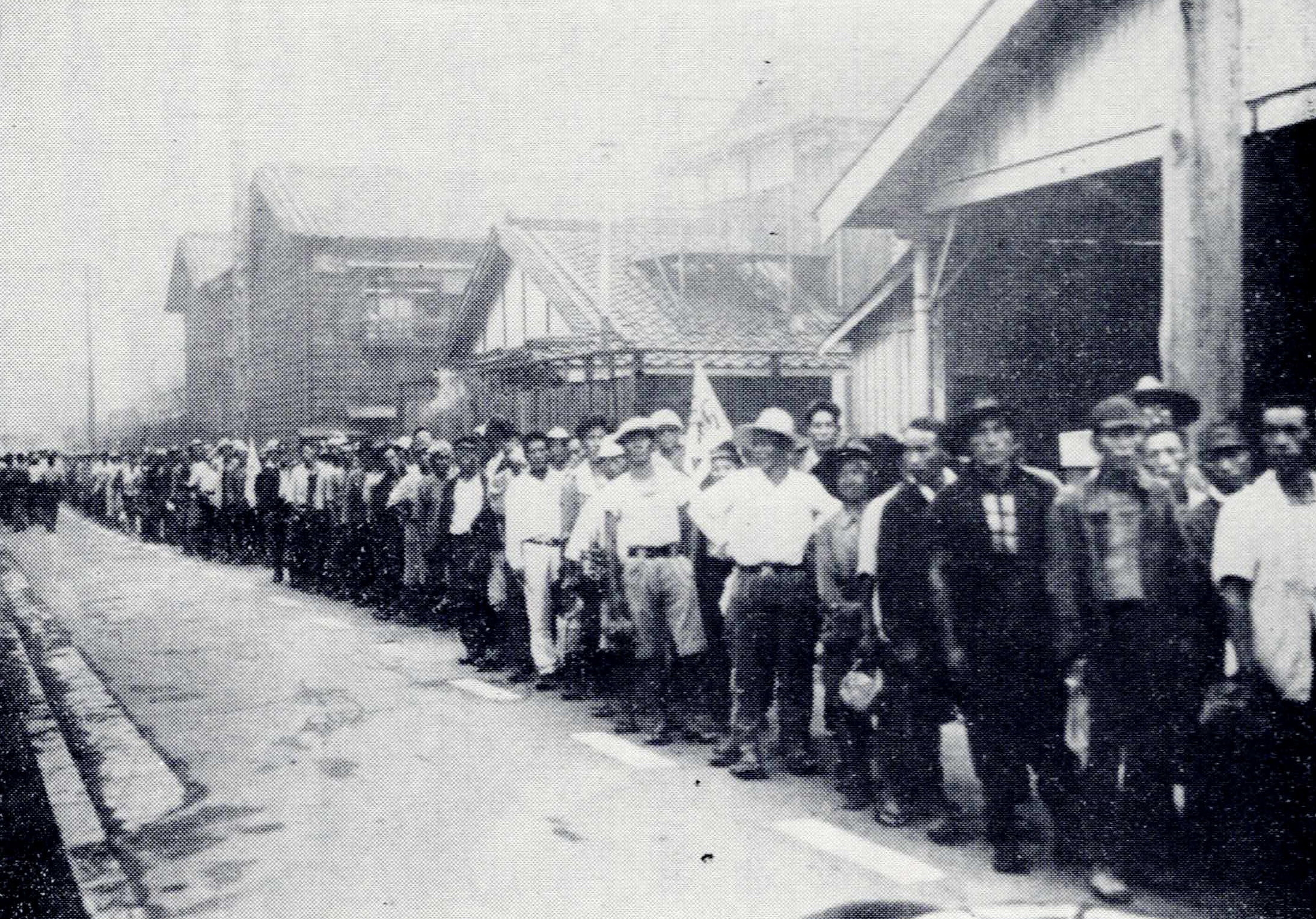

A line of laborers waiting for the day’s work

Source: Osaka City Port Authority, Osakako-Shi 3 (Osaka: Osaka City Port Authority, 1964).

At Fujinagata, the prisoner-of-war camp was located at some distance from the factory site. About one hundred fifty Australian soldiers were interned there. Since I was assigned a job at the dormitory, I did not know anything about them at all. But, every morning, I came across a team of prisoners on the walkway. Under the supervision of a detention officer carrying a wooden sword, they walked to the workplace with shovels on their shoulders. […] The prisoners I saw all had a ragged appearance, just as they did at the time of their defeat in battle. With their bushy beards, they had bloated faces due to malnutrition. They were all like giants, which rather made me feel sorry for them. I averted my eyes when I saw them coming from the other side. (Quotes from Tozaburo Ono, “Saru no Koshikake,” in vol. 3 of Ono Tozaburo Chosakushu [Chikuma Shobo, 1991], 119. [d])

Namura Zosensho-Statistical Report. Report no. 48b (22). Entry 41: Pacific Survey Reports and Supporting Records, 1928-1948. RG243: Records of the United States Strategic Bombing Survey. National Archives and Records Administration, the United States. Data from National Diet Library, Japan.

Project Intersection

In 2007, the Japanese Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry designated the former factory site of Namura Shipyard in Osaka as one of the “33 Heritage Collections of Industrial Modernization.” The site is now utilized for cultural and artistic activities as “a unique space that has been renovated to maximize its ‘potential as a ruin’.” But many of those who currently visit the former factory site for art events and other occasions are unaware of its hidden history. The factory was a site of forced labor, where a total of 803 laborers were conscripted between 1942 and 1945, and 110 Allied prisoners of war were subjected to the servitude during the war. When one confronts this past reality, it would inevitably affect one’s present perception of the old factory space. (Yoshiya Makita, “At the Intersection of the Past and Present: History and Historical Practice on the Street,” Shien 79, no. 2 [2019]: 156. [In Japanese])

Workshop “Intersection I: In-Between Art, History, and the Local”

Field Research Project “Records, Traces, and Memories”

Date: 3 February 2018

Venue: Creative Center Osaka (Old Namura Shipyard, Suminoe-ku, Osaka); waterfront districts in Osaka, Japan

Project Statement

In recent years, the Osaka Bay Area has witnessed a growing number of initiatives aimed at neighborhood revitalization through cultural and artistic programs. By repurposing former factory sites and vacant houses for creative activities, the local government, the culture foundation, and other stakeholders have continued efforts to transform the bay area into a cultural hub for artistic endeavors, thereby revitalizing local communities through the power of art. Behind these initiatives to enhance the “attractiveness” of local communities by promoting art and culture, however, old communal memories of dock laborers have gradually faded into the depths of oblivion. Focusing on the history and memory of the Osaka Bay Area, this project explores the ways to restore the historical experiences of those who have been excluded from the dominant narratives of public memory in the area through artistic practices.

In the first half of the twentieth century, the city of Osaka developed as one of the major centers of the steel and dock industry in Japan. In parallel with the territorial expansion of the Japanese empire, the city attracted a large influx of common laborers from overseas colonies. This project delves into the mechanisms of power and violence that shaped the transnational experiences of various groups who migrated to the Osaka Bay Area through historical inquiry. By examining their lives on the social periphery in the bay area, we seek new modes of artistic practice that would challenge, reshape, and reimagine the local constellation of collective memories. Instead of giving tacit approval to the dominant narratives of public memory established by majority groups in the area, this project highlights the potential for artistic creation to destabilize the foundations of existing public memory from the perspectives of those on the fringes of local society.

Industrial plants along Kizugawa River

Source: Governor’s Office, Graph Osaka (Osaka: Public Information Division, November 1967).

Over the past decades, numerous art projects have aimed to foster close “connections” between their artistic endeavors and local communities, crystallizing into a growing number of “community art” and “memory art” pieces inspired by local history. Yet, the life stories of minority groups have frequently become invisible in these site-specific artworks. Art projects have tended to prioritize maintaining harmonious relationships with local residents and therefore have been inclined to avoid critical reading of history that would provoke confrontations with majority groups in local communities. Consequently, they have often overlooked the exclusive nature of the dominant public memory in these communities and have failed to critically address the tensions between art, history, and society. With a strong aspiration to be “community-based,” these projects have too readily endorsed the prevailing historical interpretations of local communities, inadvertently reinforcing the existing “master narratives” of local history.

This project uncovers the hidden complicity between certain trends in art projects and the conventional narratives of local history and memory in Japan. Reconsidering the seemingly stable identity of local communities through historical research, we seek to illuminate new directions in artistic practices for more critical engagement with social issues. Marked by the harsh violence of colonialism in the past and the advancement of creative initiatives in the present, the Osaka Bay Area offers a unique vantage point to envision new possibilities in socially engaged art and culture.

Workshop “Intersection I: In-Between Art, History, and the Local” (3 February 2018). Photo by Masaki Komori

Workshop “Intersection I: In-Between Art, History, and the Local”

Panelists: Hikaru Fujii, Yuki Harada, Yuki Iiyama, and Sen Uesaki

Moderators: Masaki Komori and Yoshiya Makita

Organizers: Project Intersection Planning Committee (Masaki Komori and Yoshiya Makita); Makita Yoshiya Research Seminar (AY2017-2018), College of Policy Science, Ritsumeikan University

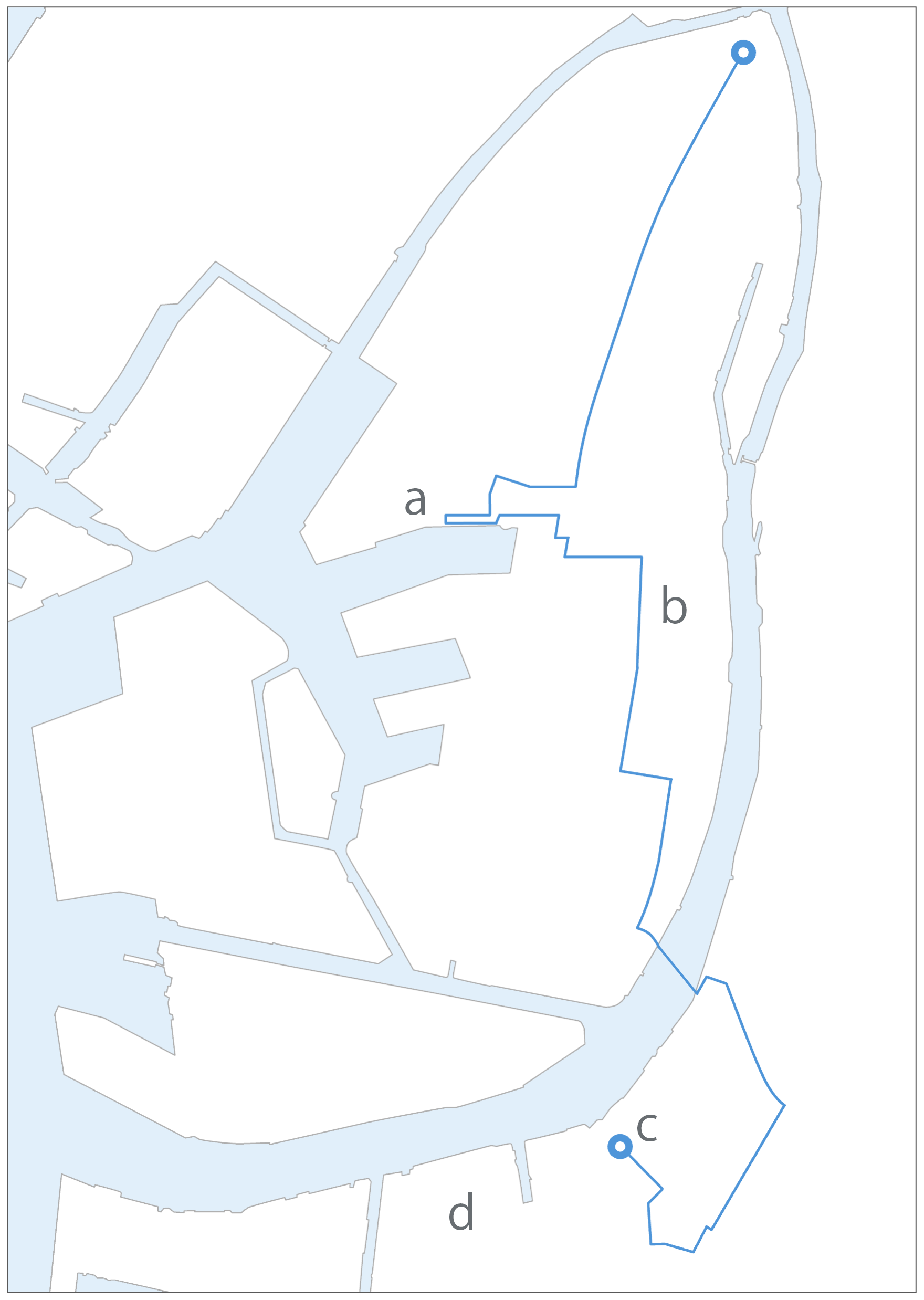

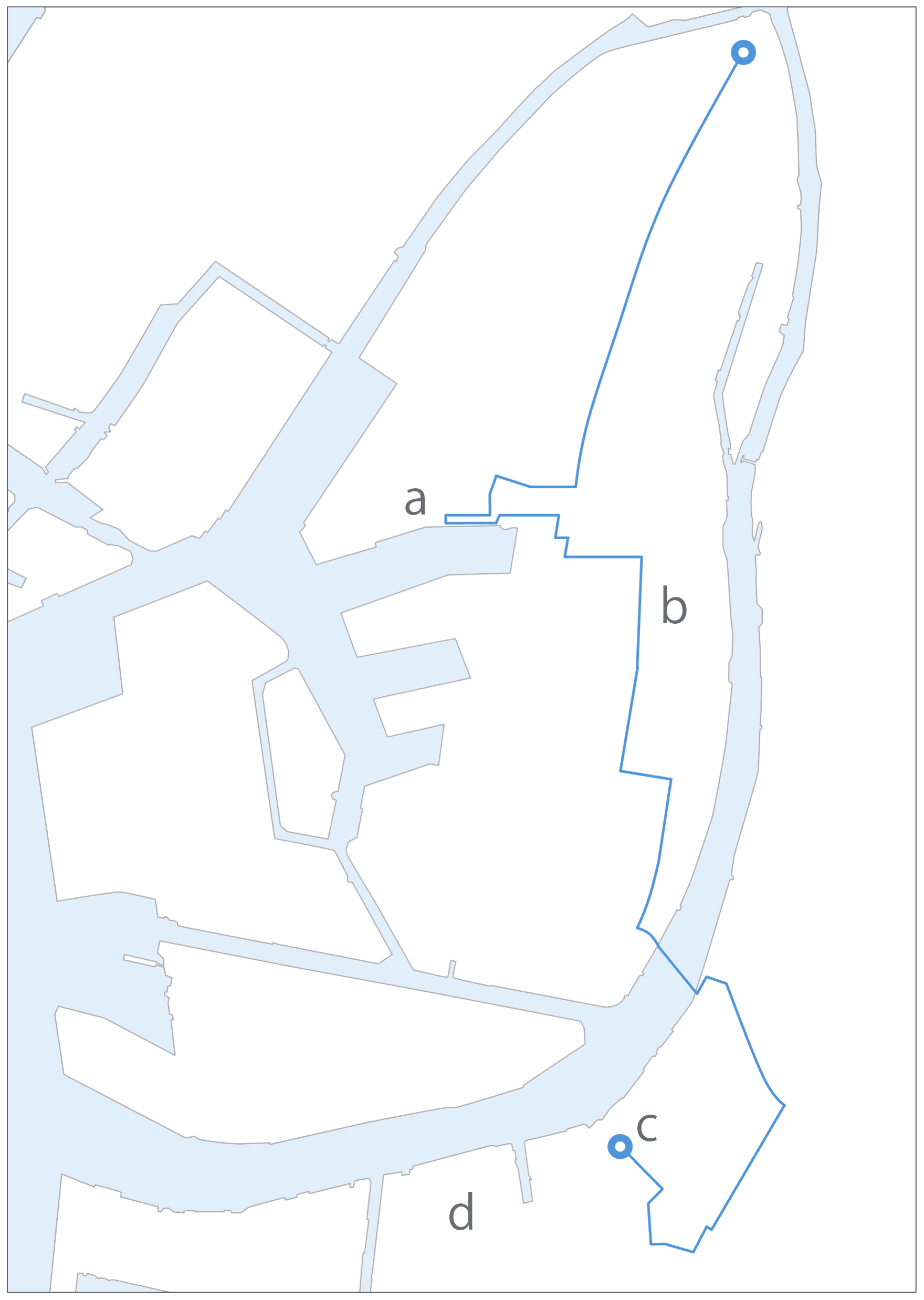

Field Research Project “Records, Traces, and Memories”

“Exploring traces of the past within the present landscape and creating a new constellation of memories through historical records”

Fieldwork and on-site workshop

Moderators: Hikaru Fujii and Yoshiya Makita

Date: 3 February 2018, 10:00-13:30

Place: Taisho-ku and Suminoe-ku, Osaka City, Osaka

In the southwestern part of Osaka City, there is a block known as “Okinawa Slum” in a corner of Taisho Ward. Shacks are crowded on the marshy land, where about 1,500 people live, packed closely together. Approximately 30% of the residents are from Okinawa. […] Twenty-three years have passed since Japan’s defeat in the previous war. Even after the restoration of independence on Japan’s mainland, the occupation has continued in Okinawa. The island has been left separated from the homeland. For its nine hundred thousand residents, as well as for the entire nation, the reversion to the homeland is a long-cherished dream. But what if the slums are the only refuge for those who left their island and returned to the homeland ahead of others… This reality seems symbolic of a deep divide that lies between the mainland and Okinawa. (Quotes from Asahi Shinbun [15 July 1968]. [a])

“Kubungwa,” an Okinawan village in Taisho Ward, Osaka City, in the 1960s

Source: Asahi Shinbun (15 July 1968).

And there was a vast vacant lot to the east of the village. The lot was called Akaba, a site used for garbage dumping and incineration. A uniquely strong burning smell spread all around. But once I got used to it, I didn’t mind it so much. In fact, this garbage dump is closely related to the lives of people in the Korean village. / Aka meant copper. The Koreans in the village collected and sold copper wire, iron scraps, shards of other metals, and pieces of glass from the ashes and burnt residue. This turned out to be quite a good source of income. (Quotes from Choi Sukeui, Zainichi no Genfukei: Rekishi, Bunka, Hito [Akashi Shoten, 2004], 13. [b])

“Sanoyasu the Devil, Namura of Hell, and Merciless Fujinagata.” This was a catchphrase I often heard. Was this just the cynicism of Osaka folks making fun of the winners, or did it actually reflect some truth? It may sound quite convincing to those who are personally familiar with the shipyards that once stood along Kizugawa River. (Quotes from Kazuo Sugiyama, “Kawasuji no Zosenya: Namura Gennosuke-okina no Sokuseki,” Koseki: Sensho tachi kara Jidai heno Dengon, ed. Kansai Zosen Kyokai [Kansai Zosen Kyokai Soritsu 90 Shunen Kinenshi, 2002], 37. [c])

Lumber workers on water

Source: Osaka City Port Authority, Osakako-Shi 3 (Osaka: Osaka City Port Authority, 1964).

In 1912, I was born as the eldest son of a poor peasant family in North Gyeongsang Province. In 1927, when I was fifteen years old, I came to Japan in search of work. I lived in Osaka, where I worked hard and attended evening classes. It was a difficult time, but I was happy because I was with my family. / Yet, it only lasted for a short period of time. In 1942, a year after the war started, I was taken to Namura Shipyard, a munitions factory in Osaka. The factory was a military-style structure for labor. It was tough for me. (Quotes from Park Seongchaek, “Kako heno Shin no Hansei wo: Osaka Namura Zosen,” Chosenjin Kyosei Renko no Kiroku: Chubu, Tokai Hen, ed. Chosenjin Kyosei Renko Shinso Chosadan [Kashiwa Shobo, 1997], 292. [c])

A line of laborers waiting for the day’s work

Source: Osaka City Port Authority, Osakako-Shi 3 (Osaka: Osaka City Port Authority, 1964).

At Fujinagata, the prisoner-of-war camp was located at some distance from the factory site. About one hundred fifty Australian soldiers were interned there. Since I was assigned a job at the dormitory, I did not know anything about them at all. But, every morning, I came across a team of prisoners on the walkway. Under the supervision of a detention officer carrying a wooden sword, they walked to the workplace with shovels on their shoulders. […] The prisoners I saw all had a ragged appearance, just as they did at the time of their defeat in battle. With their bushy beards, they had bloated faces due to malnutrition. They were all like giants, which rather made me feel sorry for them. I averted my eyes when I saw them coming from the other side. (Quotes from Tozaburo Ono, “Saru no Koshikake,” in vol. 3 of Ono Tozaburo Chosakushu [Chikuma Shobo, 1991], 119. [d])

Namura Zosensho-Statistical Report. Report no. 48b (22). Entry 41: Pacific Survey Reports and Supporting Records, 1928-1948. RG243: Records of the United States Strategic Bombing Survey. National Archives and Records Administration, the United States. Data from National Diet Library, Japan.

Project Intersection

In 2007, the Japanese Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry designated the former factory site of Namura Shipyard in Osaka as one of the “33 Heritage Collections of Industrial Modernization.” The site is now utilized for cultural and artistic activities as “a unique space that has been renovated to maximize its ‘potential as a ruin’.” But many of those who currently visit the former factory site for art events and other occasions are unaware of its hidden history. The factory was a site of forced labor, where a total of 803 laborers were conscripted between 1942 and 1945, and 110 Allied prisoners of war were subjected to the servitude during the war. When one confronts this past reality, it would inevitably affect one’s present perception of the old factory space. (Yoshiya Makita, “At the Intersection of the Past and Present: History and Historical Practice on the Street,” Shien 79, no. 2 [2019]: 156. [In Japanese])

Workshop “Intersection I: In-Between Art, History, and the Local”

Field Research Project “Records, Traces, and Memories”

Date: 3 February 2018

Venue: Creative Center Osaka (Old Namura Shipyard, Suminoe-ku, Osaka); waterfront districts in Osaka, Japan

Project Statement

In recent years, the Osaka Bay Area has witnessed a growing number of initiatives aimed at neighborhood revitalization through cultural and artistic programs. By repurposing former factory sites and vacant houses for creative activities, the local government, the culture foundation, and other stakeholders have continued efforts to transform the bay area into a cultural hub for artistic endeavors, thereby revitalizing local communities through the power of art. Behind these initiatives to enhance the “attractiveness” of local communities by promoting art and culture, however, old communal memories of dock laborers have gradually faded into the depths of oblivion. Focusing on the history and memory of the Osaka Bay Area, this project explores the ways to restore the historical experiences of those who have been excluded from the dominant narratives of public memory in the area through artistic practices.

In the first half of the twentieth century, the city of Osaka developed as one of the major centers of the steel and dock industry in Japan. In parallel with the territorial expansion of the Japanese empire, the city attracted a large influx of common laborers from overseas colonies. This project delves into the mechanisms of power and violence that shaped the transnational experiences of various groups who migrated to the Osaka Bay Area through historical inquiry. By examining their lives on the social periphery in the bay area, we seek new modes of artistic practice that would challenge, reshape, and reimagine the local constellation of collective memories. Instead of giving tacit approval to the dominant narratives of public memory established by majority groups in the area, this project highlights the potential for artistic creation to destabilize the foundations of existing public memory from the perspectives of those on the fringes of local society.

Industrial plants along Kizugawa River

Source: Governor’s Office, Graph Osaka (Osaka: Public Information Division, November 1967).

Over the past decades, numerous art projects have aimed to foster close “connections” between their artistic endeavors and local communities, crystallizing into a growing number of “community art” and “memory art” pieces inspired by local history. Yet, the life stories of minority groups have frequently become invisible in these site-specific artworks. Art projects have tended to prioritize maintaining harmonious relationships with local residents and therefore have been inclined to avoid critical reading of history that would provoke confrontations with majority groups in local communities. Consequently, they have often overlooked the exclusive nature of the dominant public memory in these communities and have failed to critically address the tensions between art, history, and society. With a strong aspiration to be “community-based,” these projects have too readily endorsed the prevailing historical interpretations of local communities, inadvertently reinforcing the existing “master narratives” of local history.

This project uncovers the hidden complicity between certain trends in art projects and the conventional narratives of local history and memory in Japan. Reconsidering the seemingly stable identity of local communities through historical research, we seek to illuminate new directions in artistic practices for more critical engagement with social issues. Marked by the harsh violence of colonialism in the past and the advancement of creative initiatives in the present, the Osaka Bay Area offers a unique vantage point to envision new possibilities in socially engaged art and culture.

Workshop “Intersection I: In-Between Art, History, and the Local” (3 February 2018). Photo by Masaki Komori

Workshop “Intersection I: In-Between Art, History, and the Local”

Panelists: Hikaru Fujii, Yuki Harada, Yuki Iiyama, and Sen Uesaki

Moderators: Masaki Komori and Yoshiya Makita

Organizers: Project Intersection Planning Committee (Masaki Komori and Yoshiya Makita); Makita Yoshiya Research Seminar (AY2017-2018), College of Policy Science, Ritsumeikan University

Field Research Project “Records, Traces, and Memories”

“Exploring traces of the past within the present landscape and creating a new constellation of memories through historical records”

Fieldwork and on-site workshop

Moderators: Hikaru Fujii and Yoshiya Makita

Date: 3 February 2018, 10:00-13:30

Place: Taisho-ku and Suminoe-ku, Osaka City, Osaka

In the southwestern part of Osaka City, there is a block known as “Okinawa Slum” in a corner of Taisho Ward. Shacks are crowded on the marshy land, where about 1,500 people live, packed closely together. Approximately 30% of the residents are from Okinawa. […] Twenty-three years have passed since Japan’s defeat in the previous war. Even after the restoration of independence on Japan’s mainland, the occupation has continued in Okinawa. The island has been left separated from the homeland. For its nine hundred thousand residents, as well as for the entire nation, the reversion to the homeland is a long-cherished dream. But what if the slums are the only refuge for those who left their island and returned to the homeland ahead of others… This reality seems symbolic of a deep divide that lies between the mainland and Okinawa. (Quotes from Asahi Shinbun [15 July 1968]. [a])

“Kubungwa,” an Okinawan village in Taisho Ward, Osaka City, in the 1960s. Source: Asahi Shinbun (15 July 1968).

And there was a vast vacant lot to the east of the village. The lot was called Akaba, a site used for garbage dumping and incineration. A uniquely strong burning smell spread all around. But once I got used to it, I didn’t mind it so much. In fact, this garbage dump is closely related to the lives of people in the Korean village. / Aka meant copper. The Koreans in the village collected and sold copper wire, iron scraps, shards of other metals, and pieces of glass from the ashes and burnt residue. This turned out to be quite a good source of income. (Quotes from Choi Sukeui, Zainichi no Genfukei: Rekishi, Bunka, Hito [Akashi Shoten, 2004], 13. [b])

“Sanoyasu the Devil, Namura of Hell, and Merciless Fujinagata.” This was a catchphrase I often heard. Was this just the cynicism of Osaka folks making fun of the winners, or did it actually reflect some truth? It may sound quite convincing to those who are personally familiar with the shipyards that once stood along Kizugawa River. (Quotes from Kazuo Sugiyama, “Kawasuji no Zosenya: Namura Gennosuke-okina no Sokuseki,” Koseki: Sensho tachi kara Jidai heno Dengon, ed. Kansai Zosen Kyokai [Kansai Zosen Kyokai Soritsu 90 Shunen Kinenshi, 2002], 37. [c])

Lumber workers on water

Source: Osaka City Port Authority, Osakako-Shi 3 (Osaka: Osaka City Port Authority, 1964).

In 1912, I was born as the eldest son of a poor peasant family in North Gyeongsang Province. In 1927, when I was fifteen years old, I came to Japan in search of work. I lived in Osaka, where I worked hard and attended evening classes. It was a difficult time, but I was happy because I was with my family. / Yet, it only lasted for a short period of time. In 1942, a year after the war started, I was taken to Namura Shipyard, a munitions factory in Osaka. The factory was a military-style structure for labor. It was tough for me. (Quotes from Park Seongchaek, “Kako heno Shin no Hansei wo: Osaka Namura Zosen,” Chosenjin Kyosei Renko no Kiroku: Chubu, Tokai Hen, ed. Chosenjin Kyosei Renko Shinso Chosadan [Kashiwa Shobo, 1997], 292. [c])

A line of laborers waiting for the day’s work

Source: Osaka City Port Authority, Osakako-Shi 3 (Osaka: Osaka City Port Authority, 1964).

At Fujinagata, the prisoner-of-war camp was located at some distance from the factory site. About one hundred fifty Australian soldiers were interned there. Since I was assigned a job at the dormitory, I did not know anything about them at all. But, every morning, I came across a team of prisoners on the walkway. Under the supervision of a detention officer carrying a wooden sword, they walked to the workplace with shovels on their shoulders. […] The prisoners I saw all had a ragged appearance, just as they did at the time of their defeat in battle. With their bushy beards, they had bloated faces due to malnutrition. They were all like giants, which rather made me feel sorry for them. I averted my eyes when I saw them coming from the other side. (Quotes from Tozaburo Ono, “Saru no Koshikake,” in vol. 3 of Ono Tozaburo Chosakushu [Chikuma Shobo, 1991], 119. [d])