Memory of the Soil / History of the Mountain

Exhibition

Date: 23-25 September 2017

Venue: Ibaraki Sky Palette. Ibaraki, Osaka, Japan

Project Statement

How does understanding the past of a place affect our present perception of that place? Guided by this question, Memory of the Soil / History of the Mountain delves into the history and memory of the northern mountain area of Ibaraki in Osaka, Japan.

The mountain area of northern Ibaraki currently faces significant social challenges. Although the northern mountain area accounts for approximately half of Ibaraki’s total land, the mountain population makes up less than 1% of the city’s total. Alongside the population outflow to urban districts in southern Ibaraki and adjacent cities, the declining birthrate and aging population have eroded the social foundations of the northern mountain communities. Simply put, village communities in the mountain area are now on the brink of collapse. As local communities deteriorate, preserving the history and memory of these mountain villages has also become increasingly difficult.

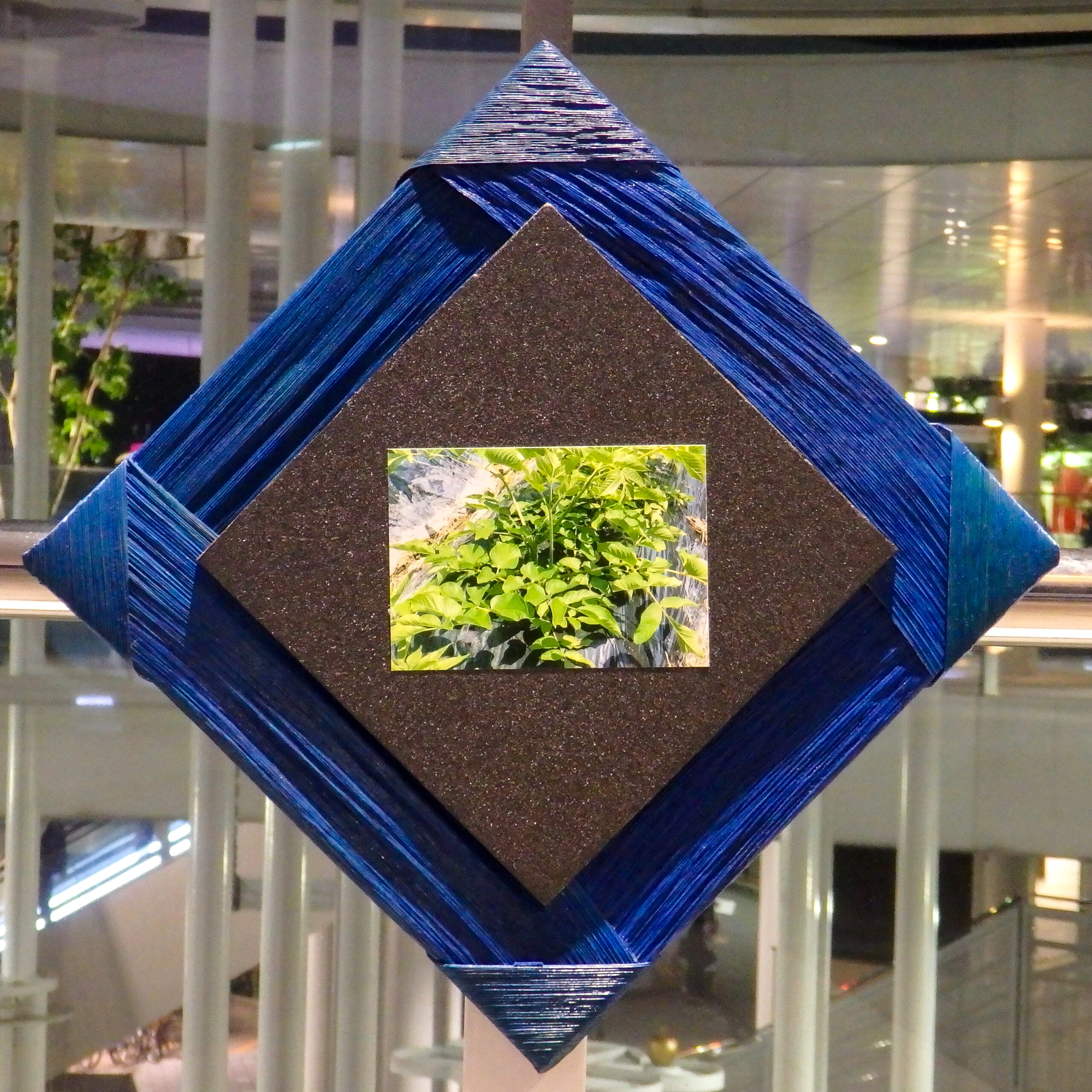

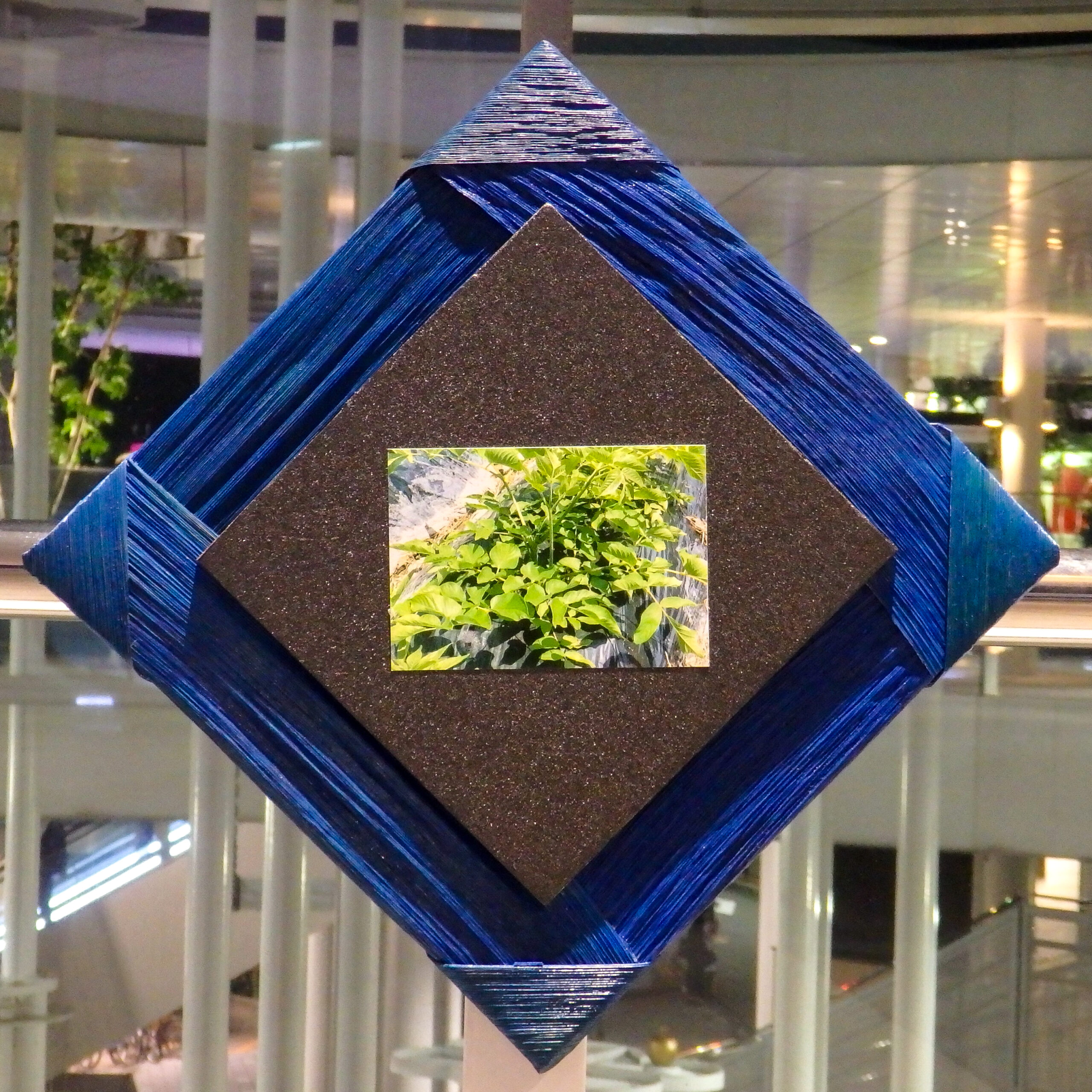

In the course of field research, we ventured into the northern mountains in search of historical traces of what once existed in the area. Then, using piles of bamboo bark collected from the mountains, we created 95 panels that tell the history and memories of the area.

While maintaining close socio-economic ties with the urban area in the south, the mountain area in the north has long nurtured unique life-cultures in abundant nature. When we unravel its history, we realize that the northern mountain area has never been culturally homogeneous. Rather, the area is characterized by the diversity of cultures that evolved in each village community. By focusing on these diverse cultures in the mountain area, this exhibition illuminates the unique histories of village communities that developed behind the seemingly monotonous mountain landscape.

In modern and contemporary Japan, the government repeatedly redrew the borders of regions and municipalities from the introduction of the town and village system during the Meiji period until the “Heisei Great Mergers” at the turn of the twenty-first century. In the process of merger and consolidation of municipalities, diverse communities with different political, economic, and cultural backgrounds were integrated into larger administrative areas. This was also the case for Ibaraki, which developed through the consolidation of various communities in the north and south.

The institutional changes in local administrative divisions have exerted both direct and indirect influence on people’s perceptions of the areas in which they lived. As small villages were merged into larger municipalities, former villagers gradually acquired a new identity as citizens of the broader administrative area. This process, in turn, expanded and added complexity to their views of “locality.” Consequently, the scope and content of what we understand by the term “local” have fluctuated historically.

Shimo-Otowa Village. Source: Governor’s Office, Graph Osaka (Osaka: Public Information Division, March 1964).

What does the “local” mean? Where can we find it? For many people, including those of us living in the southern urban area of Ibaraki, the northern mountain area has not always been a familiar place. How does understanding the history and memory of the “other half” of the city bring about changes in our perceptions of the “local”? By shedding new light on the diverse historical heritages in the mountain area of Ibaraki, this exhibition illustrates the intension and extension of the word “local” from historical perspectives.

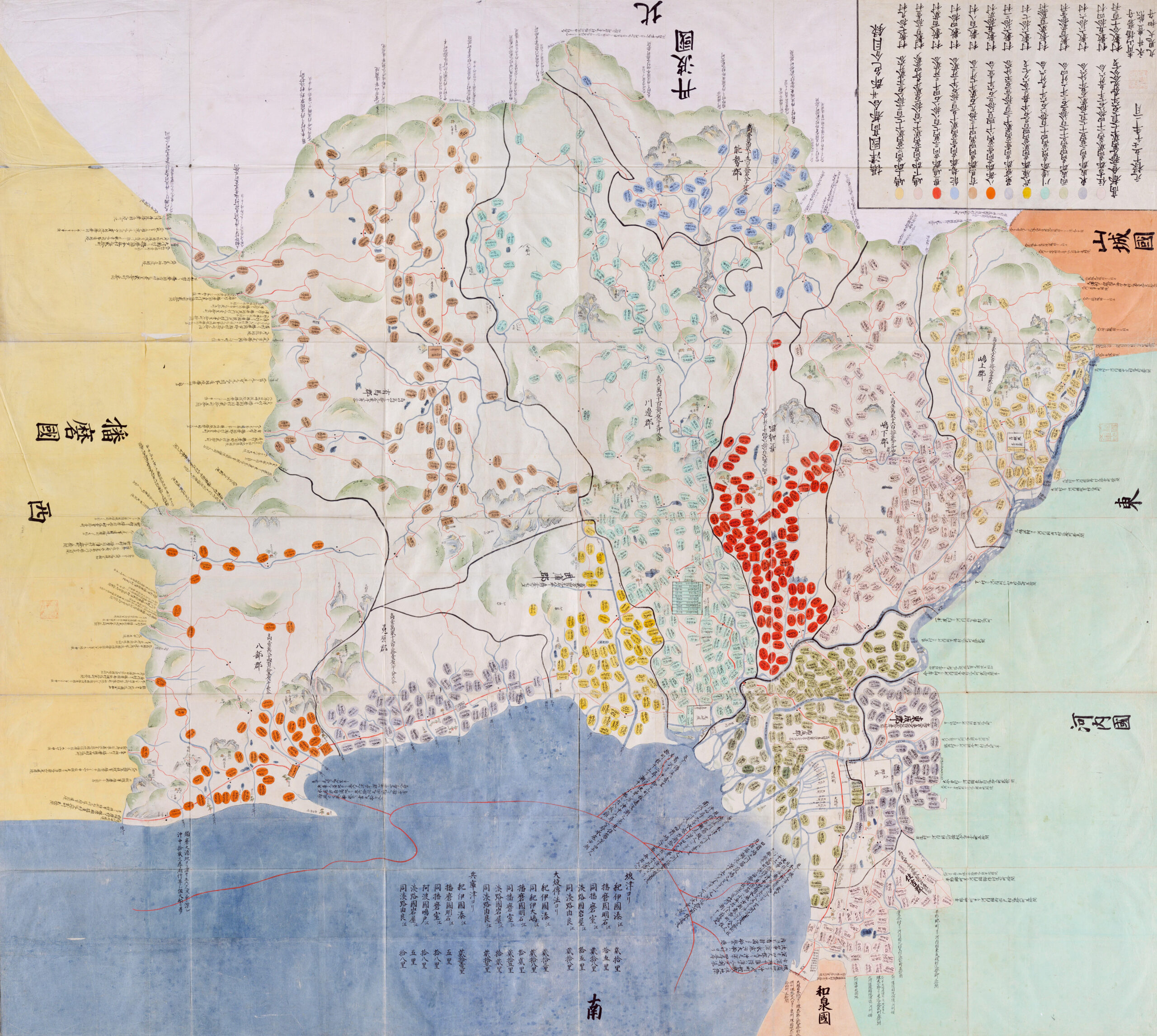

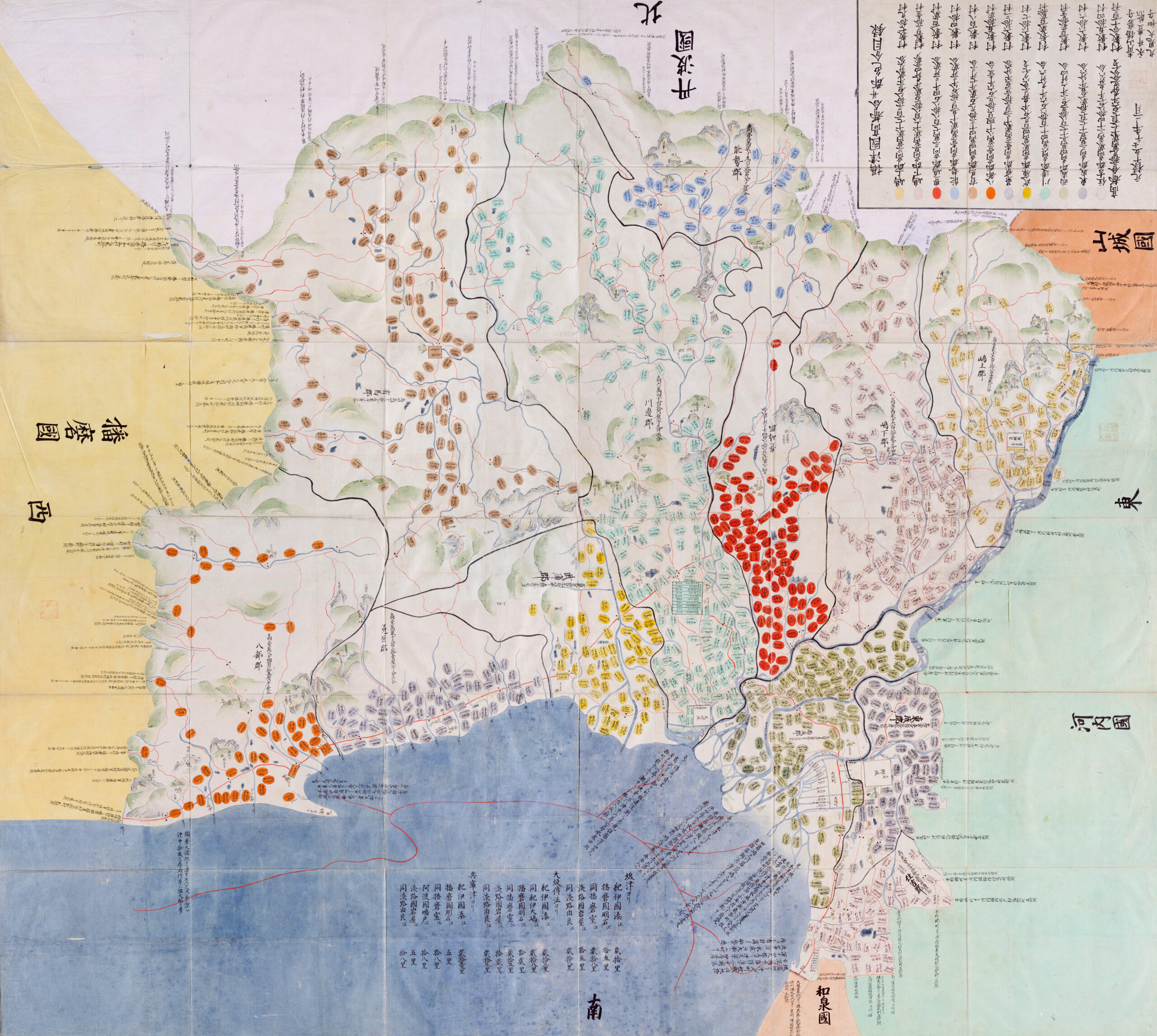

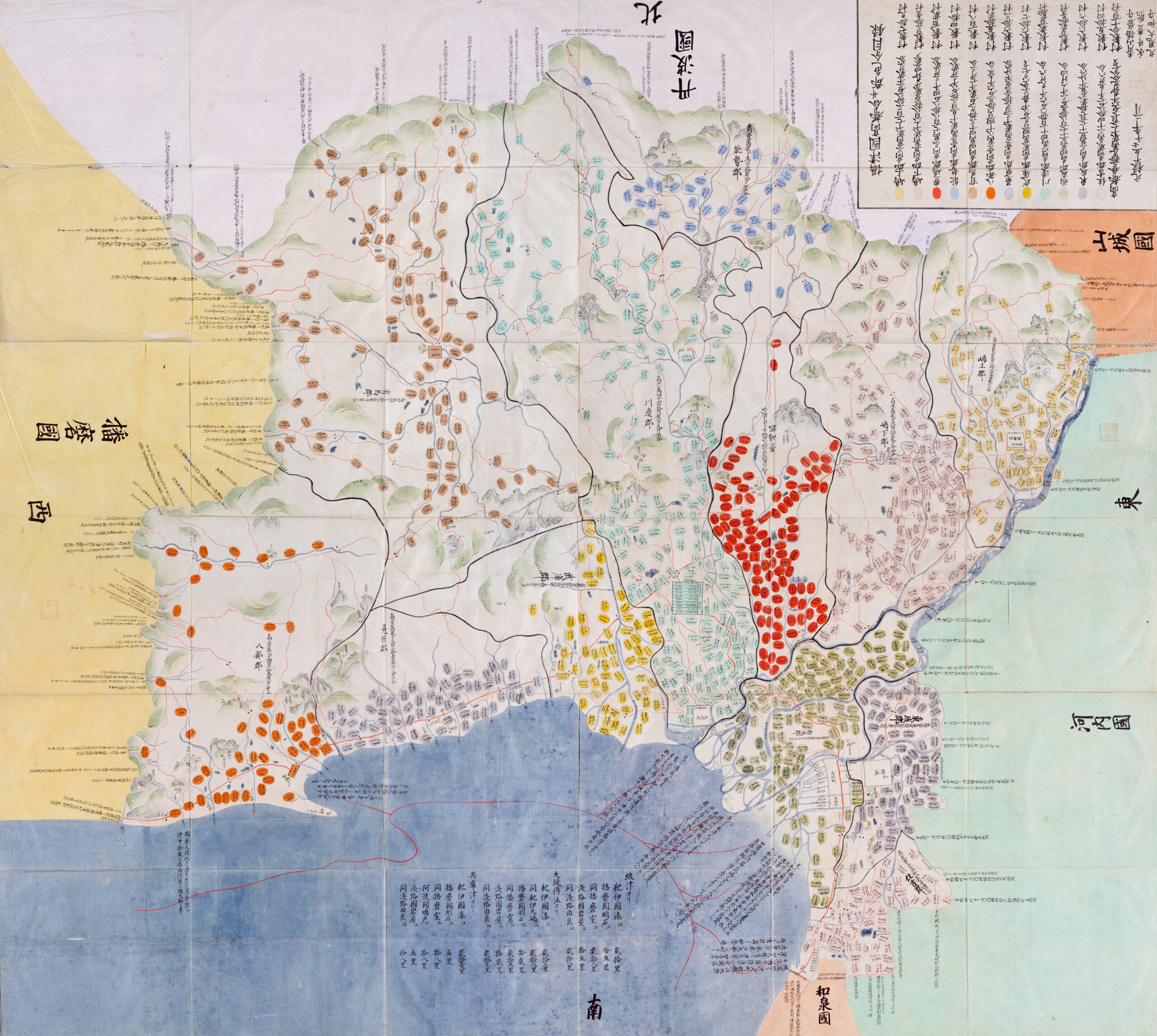

“Local communities” in North Osaka at the end of the seventeenth century

Source: Genroku Kuniezu Settsu-no-Kuni (1696). National Archives of Japan

Memory of the Soil / History of the Mountain (2017)

Organized by Makita Yoshiya Research Seminar (AY2017-2018), College of Policy Science, Ritsumeikan University

Sponsored by Ibaraki City (“Social Experiment to Open Spaces” Program)

Supported by Ibaraki Hokuchi no kai; OIC Office of Regional Collaboration, Ritsumeikan University

Memory of the Soil / History of the Mountain

Exhibition

Date: 23-25 September 2017

Venue: Ibaraki Sky Palette. Ibaraki, Osaka, Japan

Project Statement

How does understanding the past of a place affect our present perception of that place? Guided by this question, Memory of the Soil / History of the Mountain delves into the history and memory of the northern mountain area of Ibaraki in Osaka, Japan.

The mountain area of northern Ibaraki currently faces significant social challenges. Although the northern mountain area accounts for approximately half of Ibaraki’s total land, the mountain population makes up less than 1% of the city’s total. Alongside the population outflow to urban districts in southern Ibaraki and adjacent cities, the declining birthrate and aging population have eroded the social foundations of the northern mountain communities. Simply put, village communities in the mountain area are now on the brink of collapse. As local communities deteriorate, preserving the history and memory of these mountain villages has also become increasingly difficult.

In the course of field research, we ventured into the northern mountains in search of historical traces of what once existed in the area. Then, using piles of bamboo bark collected from the mountains, we created 95 panels that tell the history and memories of the area.

While maintaining close socio-economic ties with the urban area in the south, the mountain area in the north has long nurtured unique life-cultures in abundant nature. When we unravel its history, we realize that the northern mountain area has never been culturally homogeneous. Rather, the area is characterized by the diversity of cultures that evolved in each village community. By focusing on these diverse cultures in the mountain area, this exhibition illuminates the unique histories of village communities that developed behind the seemingly monotonous mountain landscape.

In modern and contemporary Japan, the government repeatedly redrew the borders of regions and municipalities from the introduction of the town and village system during the Meiji period until the “Heisei Great Mergers” at the turn of the twenty-first century. In the process of merger and consolidation of municipalities, diverse communities with different political, economic, and cultural backgrounds were integrated into larger administrative areas. This was also the case for Ibaraki, which developed through the consolidation of various communities in the north and south.

The institutional changes in local administrative divisions have exerted both direct and indirect influence on people’s perceptions of the areas in which they lived. As small villages were merged into larger municipalities, former villagers gradually acquired a new identity as citizens of the broader administrative area. This process, in turn, expanded and added complexity to their views of “locality.” Consequently, the scope and content of what we understand by the term “local” have fluctuated historically.

Shimo-Otowa Village. Source: Governor’s Office, Graph Osaka (Osaka: Public Information Division, March 1964).

What does the “local” mean? Where can we find it? For many people, including those of us living in the southern urban area of Ibaraki, the northern mountain area has not always been a familiar place. How does understanding the history and memory of the “other half” of the city bring about changes in our perceptions of the “local”? By shedding new light on the diverse historical heritages in the mountain area of Ibaraki, this exhibition illustrates the intension and extension of the word “local” from historical perspectives.

“Local communities” in North Osaka at the end of the seventeenth century

Source: Genroku Kuniezu Settsu-no-Kuni (1696). National Archives of Japan

Memory of the Soil / History of the Mountain (2017)

Organized by Makita Yoshiya Research Seminar (AY2017-2018), College of Policy Science, Ritsumeikan University

Sponsored by Ibaraki City (“Social Experiment to Open Spaces” Program)

Supported by Ibaraki Hokuchi no kai; OIC Office of Regional Collaboration, Ritsumeikan University

Memory of the Soil / History of the Mountain

Exhibition

Date: 23-25 September 2017

Venue: Ibaraki Sky Palette. Ibaraki, Osaka, Japan

Project Statement

How does understanding the past of a place affect our present perception of that place? Guided by this question, Memory of the Soil / History of the Mountain delves into the history and memory of the northern mountain area of Ibaraki in Osaka, Japan.

The mountain area of northern Ibaraki currently faces significant social challenges. Although the northern mountain area accounts for approximately half of Ibaraki’s total land, the mountain population makes up less than 1% of the city’s total. Alongside the population outflow to urban districts in southern Ibaraki and adjacent cities, the declining birthrate and aging population have eroded the social foundations of the northern mountain communities. Simply put, village communities in the mountain area are now on the brink of collapse. As local communities deteriorate, preserving the history and memory of these mountain villages has also become increasingly difficult.

In the course of field research, we ventured into the northern mountains in search of historical traces of what once existed in the area. Then, using piles of bamboo bark collected from the mountains, we created 95 panels that tell the history and memories of the area.

While maintaining close socio-economic ties with the urban area in the south, the mountain area in the north has long nurtured unique life-cultures in abundant nature. When we unravel its history, we realize that the northern mountain area has never been culturally homogeneous. Rather, the area is characterized by the diversity of cultures that evolved in each village community. By focusing on these diverse cultures in the mountain area, this exhibition illuminates the unique histories of village communities that developed behind the seemingly monotonous mountain landscape.

In modern and contemporary Japan, the government repeatedly redrew the borders of regions and municipalities from the introduction of the town and village system during the Meiji period until the “Heisei Great Mergers” at the turn of the twenty-first century. In the process of merger and consolidation of municipalities, diverse communities with different political, economic, and cultural backgrounds were integrated into larger administrative areas. This was also the case for Ibaraki, which developed through the consolidation of various communities in the north and south.

The institutional changes in local administrative divisions have exerted both direct and indirect influence on people’s perceptions of the areas in which they lived. As small villages were merged into larger municipalities, former villagers gradually acquired a new identity as citizens of the broader administrative area. This process, in turn, expanded and added complexity to their views of “locality.” Consequently, the scope and content of what we understand by the term “local” have fluctuated historically.

Shimo-Otowa Village. Source: Governor’s Office, Graph Osaka (Osaka: Public Information Division, March 1964).

What does the “local” mean? Where can we find it? For many people, including those of us living in the southern urban area of Ibaraki, the northern mountain area has not always been a familiar place. How does understanding the history and memory of the “other half” of the city bring about changes in our perceptions of the “local”? By shedding new light on the diverse historical heritages in the mountain area of Ibaraki, this exhibition illustrates the intension and extension of the word “local” from historical perspectives.

“Local communities” in North Osaka at the end of the seventeenth century

Source: Genroku Kuniezu Settsu-no-Kuni (1696). National Archives of Japan

Memory of the Soil / History of the Mountain (2017)

Organized by Makita Yoshiya Research Seminar (AY2017-2018), College of Policy Science, Ritsumeikan University

Sponsored by Ibaraki City (“Social Experiment to Open Spaces” Program)

Supported by Ibaraki Hokuchi no kai; OIC Office of Regional Collaboration, Ritsumeikan University